By Jeff Keeling

The face of health care in the greater Tri-Cities is taking on a distinctively state-regulated appearance as Mountain States Health Alliance and Wellmont Health System draw closer to applying to Tennessee and Virginia for approval of their proposed merger. Activity is ramping up at both states’ departments of health and attorney generals’ offices in anticipation of an activist state role in any merged system’s business.

You may not have heard of Malaka Watson, Jeff Ockerman or Erik Bodin, but they represent the changing face of health care in the Tri-Cities – despite the fact they work in Nashville and Richmond.

Their jobs? Craft regulation requiring any merged system to show the state:

• What it will spend, what it will charge and what it will earn;

• What it will do, how it will do it and how it will help consumers save money and get healthier; and

• How the change for the better system leaders say they’re creating will outweigh the harm done by the fact the state is allowing the formation of a virtual monopoly.

If a Certificate of Public Advantage (COPA) is granted in Tennessee, and a Cooperative Agreement in Virginia, it will come after exhaustive work by people such as Ockerman, a Tennessee Department of Health (DOH) policy planner; Watson, a Tennessee DOH attorney; and Bodin, the director of the Virginia Department of Health’s (VDH) Office of Licensure and Certification. Two essential components – consumer protection and the betterment of population health – form the pillars of their work.

“It’s definitely uncharted territory, and it’s something new for us as well as Tennessee and the hospital systems,” Watson, who drafted Tennessee’s emergency rules, said during a late December interview with the Business Journal that also included Ockerman. “We really are trying to take a sort of panoramic approach in terms of looking at it from all angles. Population health is obviously high on the list, but balancing that with the economics and how it will impact consumers is a high priority as well, so we’re trying to make sure we have the right resources to help us effectively evaluate the application once we receive it.”

Wellmont and Mountain States are well past their initial target date (around Nov. 1, 2015) for filing a COPA application, likely owing to the endeavor’s complexity. They did, however, submit a 34-page “pre-submission report” Jan. 7. By Jan. 15, DOH had parsed it and responded with a letter containing six “observations” accompanied by department positions. Like the systems’ report, the observations ran the gamut from population health details and impacts on payers to one that stood out for its likely interest to area residents – and showed just how transparent the systems will have to be.

Wellmont and Mountain States are well past their initial target date (around Nov. 1, 2015) for filing a COPA application, likely owing to the endeavor’s complexity. They did, however, submit a 34-page “pre-submission report” Jan. 7. By Jan. 15, DOH had parsed it and responded with a letter containing six “observations” accompanied by department positions. Like the systems’ report, the observations ran the gamut from population health details and impacts on payers to one that stood out for its likely interest to area residents – and showed just how transparent the systems will have to be.

The observation notes “limited detail” of plans to reduce duplication of costs post-merger, including through job cuts. The department observes that most other hospital mergers result in a reduction of full-time equivalent positions, and says it needs additional detail. “Specifically,” the letter notes, “the department will require a good faith estimate of the number of full-time equivalent positions estimated to be eliminated each year, or if none, other plans to achieve stated efficiencies.”

Three primary tasks lie ahead of Watson, Bodin, Ockerman and their colleagues: making the rules governing a merger effective and defensible; helping their respective commissioners of health (John Dreyzehner in Tennessee and Marissa Levine in Virginia) determine whether the merger applications justify approval; and representing those commissioners in the “active state supervision” designed to protect the public and to make any merger hold up under judicial antitrust scrutiny. Both states specifically wrote or rewrote laws to allow for a merger with a clear eye toward previous federal interference (primarily from the Federal Trade Commission but also the Supreme Court) in previous mergers that reduced competition. Both states’ laws mention prominently a state policy to displace hospital competition with regulation, and actively supervise that regulation, “to promote cooperation and coordination among hospitals in the provision of health services and to provide state action immunity from federal and state antitrust law to the fullest extent possible to those hospitals…”

“The department understands the gravity of the changes that are occurring all over the country, in terms of healthcare organization and delivery of health care, and the financing environment of health care,” Ockerman said. “To take it down more to this regional level and whether approval of a COPA could strengthen the economic viability of these systems even though it weakens competition – ‘how does that end up working to the advantage of the public, especially in terms of improving population health?’ These are all questions that we have and are thinking about every day seriously.”

When Ockerman and Watson spoke with the Journal, a DOH team including planners, analysts and attorneys was in the middle of due diligence, preparing to move Tennessee’s rules from emergency to permanent status. The complexity of that task was highlighted by their acknowledgement they wouldn’t have time to respond to comments on the initial rules, draft proposed changes and hold hearings before the emergency rules expired Jan. 10. Yet with the hospital systems already well past their initial early November goal for COPA and Cooperative Agreement applications, DOH needed to keep the train on the track. So its rules became “permanent” Jan. 10, but will be subject to pending changes drafted by DOH personnel and possibly modified after public hearings.

COPAs are rare birds but this one is unique

COPAs are rare birds but this one is unique

Given the American bias toward free markets, anti-competitive hospital system mergers as significant as a Wellmont-MSHA marriage are rare. COPA laws exist in a number of states but few COPAs actually have been granted (Tennessee’s law actually existed for years before the current situation, but had never been used). Those that have, DOH’s Ockerman said, have primarily addressed consumer protection. But those, including an oft-cited one from 1995 that allowed Mission and St. Joseph’s hospitals in the Asheville, N.C. market to merge, were primarily granted before healthcare reform brought a focus on improving population health.

“Population health and access to health services as well as the economic impact on the consumers are the three primary things,” Ockerman said. “There are potentially other areas of interest that will come up, but particularly from the Department of Health’s perspective, the health of the population in that region is of really primary concern to us, and if there’s a way that we can all help improve the health statistics in that area, we’d be happy to have that be the end result.”

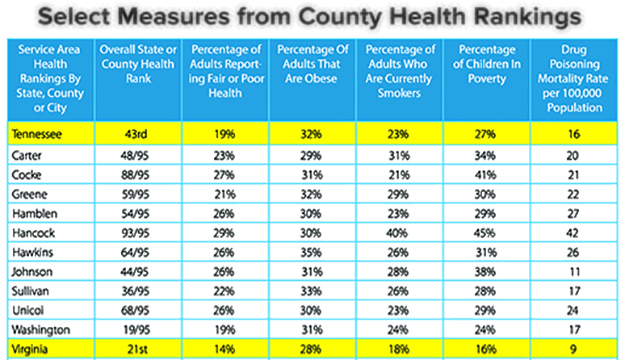

To that end, the emergency rules have significant requirements regarding the creation of measures to “continuously evaluate the Public Advantage of the results of actions approved in the COPA.” Those include improvements in the population’s health that exceed measures of national and state improvement. Similarly, the Virginia rules, which Gov. Terry McAuliffe signed into law Jan. 18, devote plenty of ink to population health. Virginia’s rules charge its health commissioner with developing the population health piece, both during selection of measures for reviewing the cooperative agreement’s proposed benefits, and during ongoing monitoring if a merger takes place. The chart on this page, which is included in the hospital systems’ pre-submission report, indicates the severity of the gap between Southwest Virginians’ population health and that of their fellow Virginians.

“Virginia has been working on … a population health improvement plan,” Bodin said in a Feb. 3 interview. “One of the things we’re looking at is how we evaluate this cooperative agreement request, and the ongoing monitoring and performance, and aligning that with that plan to see if that provides us with an opportunity.”

As early as their April 2, 2015 announcement of a planned merger, Wellmont and Mountain States mentioned a population health element. Their Jan. 7 pre-submission report outlined a four-pronged approach in its “Commitment to Improve Community Health,” on which it pledged to spend at least $75 million over 10 years.

The focus areas include “ensuring strong starts for children” with programs designed to improve measures ranging from childhood obesity and neonatal abstinence syndrome to the number of children reading on grade level by third grade; “helping adults live well in the community” with focuses on diabetes, heart disease and several cancer types; “promoting a drug free community;” and “decreasing avoidable hospital visits and ER use” by helping “high-need, high-cost” uninsured people access care at earlier stages and reduce expensive critical care use.

Community health, in turn, is one of six key areas in the report, which hints strongly at what will go in the systems’ actual applications. Other areas are enhanced health services, expanded access and choice, investing in research, attracting and retaining a strong workforce, and improving healthcare value by managing quality, cost and services.

The document concludes with big vision statements and bold claims, including that savings from reduced service duplication and improved coordination will produce annual spending designed to improve public health equivalent to the capability of a $750 million foundation. New services and capabilities, improved choice and access, managed costs and investment in addressing the region’s economic development and its most vexing health problems – all are promised results of the merger.

On the Tennessee side, DOH wants to be sure the final application (the systems’ letter of intent to file expires March 15) includes sufficient details in all aspects. In addition to its position on job reductions, the department’s other observations highlight just how activist the state will be should a merger occur. One relates to regional health and population health disparities, calling for, “granular detail” about “factors that influence the health and health disparities of counties, communities, and groups within them, particularly as it relates to the applicants’ current assessment of existing trends and long-term population health outcomes.”

The letter, signed by Allison Thigpen of the Division of Health Planning, acknowledges the systems may plan to address each observation in their final application, but wanted to alert them, “in the event you had not anticipated and addressed them in the application.”

In October 2014, Virginia Secretary of Health and Human Resources Dr. Bill Hazel addressed the changes in healthcare market dynamics, and how they might relate to a local merger request during an interview with the Business Journal. His words, which also touched on population health, seem prescient today.

“I think it probably is a reach to say the markets are working real well in health care right now, so it would not be unusual to say, then, ‘well what are our other choices?’ In Virginia we are typically market/competitive-based and that’s what I think the General Assembly thrives on. So just guessing, it would be an interesting argument to make that we should substitute a market-based economy, or a perceived market-based economy, with one that is highly regulated.”

It’s an argument Hazel’s Virginia counterpart Bodin will have a major hand in deciding.

“That’s the whole balancing act,” Bodin said. “Do the benefits afforded to the citizens outweigh the disadvantages that the loss of competition presents? In a nutshell, that’s one of the biggest evaluation points.”