By Jeff Keeling

Whatever one might choose to call it – a burr in the saddle, a thorn in the side or something else – Wellmont Health System has felt the irritating effects of a growth in “observation” patients for several years. Until the latest fiscal quarter, that is.

Following a thorough assessment of the factors behind its rising ratio of admitted patients who were given observation rather than traditional inpatient status, the system implemented a new strategy at the beginning of the 2017 fiscal year (July 1). The change is paying off big time, Wellmont CFO Todd Dougan says, both for Wellmont’s bottom line and for the patients who may have fallen into the observation camp before but whose conditions instead warranted inpatient status.

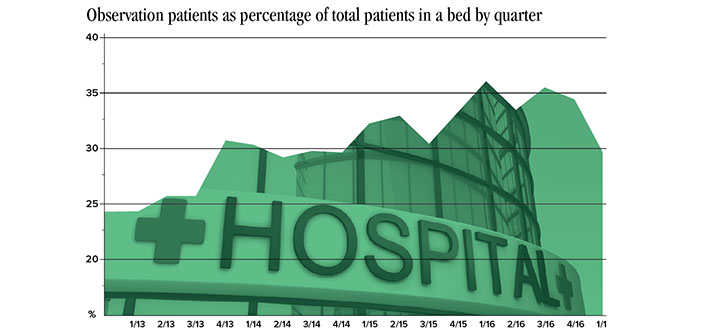

“We’re estimating that it has added about $700,000 a month in net revenue, which is about 0.6 percent on margin,” Dougan says. Given that Wellmont finished fiscal 2016 with income from operations of $12.6 million, such a gain sustained through the fiscal year would have a major impact on the system’s finances. And that is why reversing the trend of recent years (see graphic) became enough of a priority at Wellmont to get top-level administration involved last spring.

How we got here

It’s complicated. One blog summed up the origins of observation status rather plainly, though. “Obs status” originated as a way for Medicare to characterize patients who needed additional time after an emergency department stay “to sort out whether they truly needed admission,” Dr. Bob Wachter wrote in “the Health Care Blog” back in July 2013. People realized some of these patients didn’t justify an inpatient stay (usually a short one) and the rather higher reimbursements that go along with that as compared to outpatient treatment.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) set some guidelines. After all, patients who needed just a few more hours in care shouldn’t become cash cows for hospitals. The problem was that the rules were rather amorphous. So much so, Wachter wrote in his 2013 blog, that a federal investigation by an inspector general with the Department of Health and Human Services released that year found many “obs patients” and inpatients “were clinically indistinguishable.”

What had sent the pendulum swinging toward an increasing percentage of patients being deemed observation was an unintended consequence of an earlier Medicare law. The 2003 Medicare Prescription Drug Act allowed for “Recovery Audit Contractor” audits, in which auditors can observe hospital records and if they find improper billing, share in the savings. That incentive spilled over, unsurprisingly, into the rather subjective world of observation versus inpatient billing, and a few ugly RAC audits later, hospitals began erring on the side of caution. And once the private insurance companies saw what was going on, they jumped on the bandwagon, Dougan says.

A smaller reimbursement for the hospital, a bigger bill for grandma

If a decline from 37 percent of “patients in a bed” being of observation status in quarter one 2016 (July-September 2015) to 29 percent in quarter one 2017 yields roughly $2.5 million in additional net revenue, it’s pretty easy to deduce what kind of revenues were being left in the hands of payers as those percentages climbed from 27 percent in fiscal 2013 to 35 percent three years later. The system was missing out on $5 to $10 million a year in revenue at a time when other pressures were making things hard enough, Dougan says.

“The problem from a margin perspective is we are taking care of our patients and they are in an exact same bed and being taken care of by the same great people, and their status as inpatient or observation is entirely dependent on the whims of the payers.”

On top of that, observation status – even if it lasts for several days and involves expensive treatment – was a financially burdensome scenario for Medicare patients.

“The deductible or copay… generally it’s a higher copay or deductible if they’re in an outpatient setting than an inpatient setting. (Part B as opposed to Part A),” Dougan says. “They’re going to have that patient pay more of their bill as an outpatient.”

Perhaps more importantly, particularly as it relates to Medicare patients, observation patients usually don’t qualify for skilled nursing care. “They generally have to have three days of pure Medicare (Part A) in inpatient stay,” Dougan said.

“If that patient is in our bed and we’re taking care of them, but we – or the payer, and this is where the managed Medicare plans come in – says ‘no, they did not qualify for an inpatient,’ they’ve also saved money by saying that patient does not qualify to be in a skilled nursing (facility).”

Turning the ship

As Wellmont’s executive team entered its strategic planning sessions last spring, the continued rise in observation patients was top of mind. Mountain States Health Alliance had undergone a similar process a couple of years earlier and seen its observation percentage decline to a more reasonable number (from the system’s view, at least) with a concomitant improvement in revenues.

“That was one of the major operational points, and we just decided to start billing for the services in the fashion and using the medical records that we believe in and basically not using what the insurance company says,” Dougan says.

Once the decision was made, the physician clinical councils were brought into the planning process, as was a consultant specializing in case management, who highlighted areas in which Wellmont could improve its processes and documentation. It was all with an eye toward justifying more cases that fall into the gray area as inpatient rather than observation – knowing the payers wouldn’t go quietly.

Wellmont wound up splitting its case management team into two distinct areas, case management and “utilization management.”

“Their sole purpose is to work in the (emergency department) with the ED doctors to document that patient’s condition when they arrive,” Dougan says.

The full implementation of EPIC as Wellmont’s electronic medical record system has helped, too, as staff can input paramedics’ reports into the system in real time.

“All of that provides a better medical record, and it shows, really, did that patient meet that criteria as an inpatient, or are they truly observation. We still have a fairly good number of patients who are observation,” Dougan says, adding that the recommended industry standard is around 25 percent. “We’re not trying to change the rules, we’re just documenting and we’re going to enforce the rules.”

It’s business

So far, though the payers have challenged some of the calls, “they’re not denying everything,” Dougan says. “That tells me we’re doing a great job documenting and supporting the patients’ medical condition.”

And the cases they do challenge can be taken to the Department of Insurance or the courts by Wellmont.

“I’ve met with our bigger payers and said, ‘we’ll have some disagreements.’ I don’t hide. I tell them … we’re going to fight for our rights and for our patients’ rights.”

The numbers are looking even better midway through the second quarter, Dougan says. “My expectation is that we’ll improve upon that 29 percent. I try not to do forward-looking, but I think we’ll be knocking on the door of that 25 percent best performer.”

While the top-line cost in caring for patients remains roughly the same, the debut of utilization review carried some cost. Even accounting for that, the trend change is leaving Wellmont $700,000 to the good each month. That simply points to what in its rather technocratic narrative in management discussion and analysis of the quarter Wellmont referred to as “an initiative to bill in accordance with the patients’ condition and challenge the payor’s unjustified denials.”

“This is the unfortunate part of health care in the U.S,” Dougan said. “We staff up for battles. The payers have been staffed up forever. The payers generally have a 10 or 12 percent overhead load and most of that is spent on administering claims. We’re not spending anything like that. We’ve got some very good nurses (performing utilization review), but it’s nothing like $700,000 a month that we’re paying the nurses.”

Jeff Keeling is vice president of communications for

Appalachian Community Federal Credit Union.